All products and services featured are independently chosen by editors. However, Billboard may receive a commission on orders placed through its retail links, and the retailer may receive certain auditable data for accounting purposes.

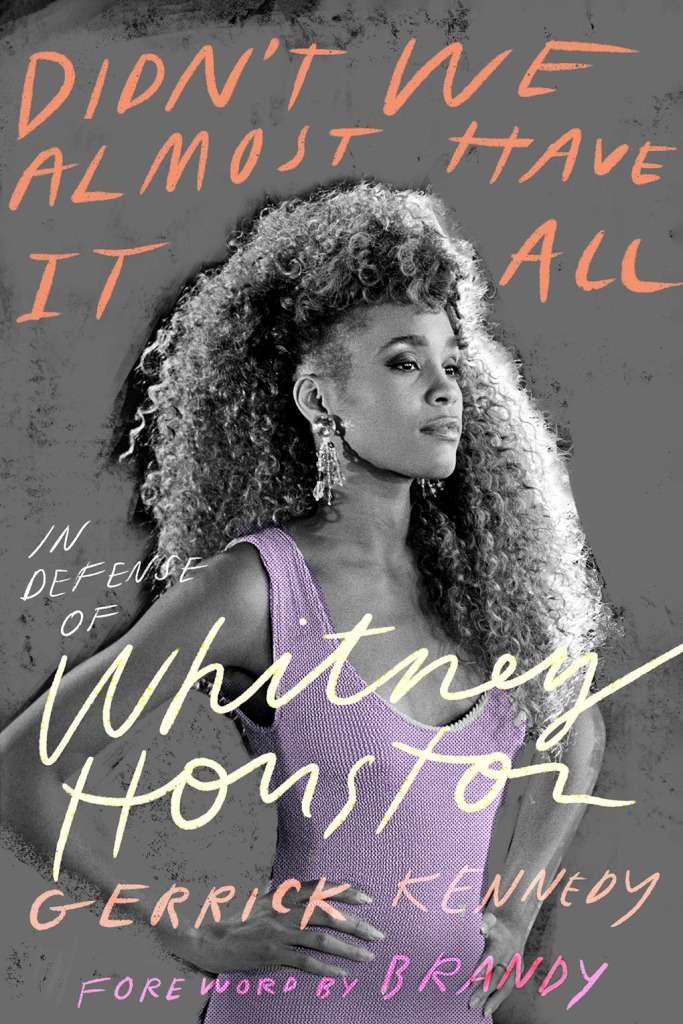

Feb. 11 marks 10 years since the death of Whitney Houston. The dualities of the multiplatinum selling singer’s life — both inside and outside of the spotlight — are explored in the new book Didn’t We Almost Have It All: In Defense of Whitney Houston by Gerrick Kennedy, with a forward by Brandy. The book will be released on Tuesday (Feb. 1).

Here, Kennedy tells Billboard about why he wanted to take on this project:

What is it about Whitney that made you want to share her story?

The question I’m asked the most is why I wanted to write a book on Whitney Houston. For me the answer was quite simple: there wasn’t a book about her that was grounded in scholarship and reverence. As someone who loved her, deeply, that felt incredibly unfair to the brilliance she blessed the world with.

So much of our understanding of Whitney, and her story, is rooted in triumph and tragedy. The world loved her, but she was also incredibly mistreated by the media and by the public. My biggest apprehension is people hear you’re writing a book on Whitney and make assumptions that it’s an exposé or it’s uncovered some new detail in the tragedies that have unfortunately come to define her. I wanted to write the book I wanted to read on Whitney, one that explored her importance and searched for meaning in her triumphs and tragedies.

It’s a love letter to Whitney, but it’s also a reflection of how far we’ve evolved culturally since losing her.

What’s one thing that you were surprised to learn about her while researching and writing the book?

I spent years researching the book — watching old interviews, reading media coverage from her rise through her passing, and after, scouring YouTube and fan sites for everything. As a fan, the things that surprised me were discovering little details on how certain songs came together that I never knew growing up. But there was a central theme that became clear as I went through the annals of Whitney coverage. I started to see how “shame” was a throughline of her life and career. Not just the shame Whitney carried or hid behind that we saw in her personal struggles, but the shame we projected onto her with our expectations and judgment. I found it surprising that we didn’t call this out more while she was here to hear it.

Buy: Didn’t We Almost Have It All: In Defense of Whitney Houston ($25)

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

Whitney will always be unknowable in a sense. She’s not here to tell us the totality of her story. I wish she were here to see this era of reconsideration we’re giving to our icons that have been mistreated. I wish she had the chance to make the documentary she wanted or write a memoir if she wanted. But she’s not, and I know I’m not the only one who will always grieve that. This book is a celebration of a generational talent the world will never see again and a reminder that she was so much more than her triumphs and tragedies. There’s two lines in the first chapter that inspired the title and is ultimately what I hope readers take away from the book: We’ll never know what could have been. But didn’t we almost have it all?

Below is an exclusive excerpt from the book’s chapter titled “Bolder, Blacker, Badder: The Sisters With Voices That Transformed Whitney.”

In our era of digitally assisted remembrance, Whitney Houston occupies a space that eluded her in life. A space where her Blackness is admired, never doubted. A glimpse of Whitney frozen in time or on a continuous loop is probably deep in your camera roll or stored among your most used GIFs. And if you don’t have Whitney saved to be at your disposal, she’s certainly graced your Twitter or Instagram feed or popped up in a group chat with your friends — craning her neck dramatically, or rolling her eyes, or looking exasperated or declaring, “Ahhh, that’s history” in the most pleasing manor. In death, through the permanence of memes, Whitney has become an auntie to all of us. It was always there, of course. Beneath the politesse, sequined gowns, and sugary pop confections that made her Whitney Houston was a round-the-way girl. But the diva hunger games that kept us bent on stacking her against Madonna, Janet, Paula, and Mariah as they all climbed the pop ladder made us overlook the idea of sisterhood that was integral to Whitney’s position in the music industry throughout her career.

The greatest Whitney GIF of all time — okay, maybe not the greatest, but certainly a Top 5 contender — was born out of the very sisterhood she held so dear. You’ve seen it. Natalie Cole is clutching the American Music Award she bested Whitney (and Paula Abdul) for as they laugh and point at each other, Natalie from the stage in her black sequined gown and gloves, and Whitney from her seat. “I don’t know how many times that Whitney and I have been in the same category together,” Natalie says at the beginning of her acceptance speech, locking eyes with her girl Whitney, “but I’m gonna enjoy this one!” It’s a beautiful image. This was 1992, and these were two pop powerhouses relishing in their success, but they were also Black women who were good girlfriends very publicly rooting for each other in a hellish industry that endlessly judged women against one another. Whitney and Natalie were entertainers who descended from music royalty, which magnified the pressures that came with their career and contributed to their struggles with drug dependency. They were women trying to make it — and left us far before they should have. I keep the GIF of Whitney and Natalie in my arsenal anytime I want to gas up one of my friends. Anytime I want to punctuate a “yass” or give praise to a shady read or a good word, I turn to that moment of Whitney and Natalie joy¬ously showing each other love. Whenever I look at it, my mind tries to place them here now, as if they were still here, competing for awards and giving us more joyful moments like the one they shared at the American Music Awards in 1992.

Sisterhood was so deep at the core of who Whitney was and how she moved in the industry. It’s what I’ve appreciated most about her, outside of any of her talents. As she got older, Whitney’s embracement of sisterhood showed an accessibility that her music and public-facing image had lacked in the beginning of her career. The way she uplifted Brandy and Monica in her name; how she embraced Kelly Price and Faith Evans and Deborah Cox; her deep friendships with Mariah and Mary J. Blige and CeCe Winans and Pebbles. The way she allowed herself to be vulnerable with Oprah Winfrey and talk about hitting rock bottom and the worst of her years with Bobby. We came to see Whitney as the quintessential Black auntie. And those GIFs of her being funny and shady that are frozen in our phones or the phrases she’s uttered that have embedded themselves in our psyche and become part of our vernacular all come from this period that I like to call the emergence of Auntie Nippy.

Before Whitney recorded the boldest (and most undeniably Black) music of her career, she filmed Waiting to Exhale. The adaptation of Terry McMillan’s bestselling tome centers sisterhood in its story of the trials and tribulations of modern Black women navigating romantic and familial relationships. Whitney had reached her zenith after singing the national anthem and followed that with the blockbuster success of The Bodyguard and its record-breaking soundtrack. For her next film role, she wanted something more complex. Something more real. Something that allowed her to show up onscreen as more than Whitney Houston, the pop diva. She found that in Waiting to Exhale. Terry McMillan writes beautifully and honestly about contemporary Black women. She writes of women who put their pain and desires on display; who live boldly or recklessly and are hopelessly looking for love, or at the very least a good lay; women who are trying to have it all in a world that doesn’t always have it for them. McMillan spoke directly, and frankly, to Black women looking to get their groove back. She wrote for the women who were sick of trifling-ass men; the women who had been in Sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots; and the women who were in search of sexual freedom and personal liberation. Waiting to Exhale, her third novel, focused on a quartet of middle-class, thirtysomething Black women in the throes of emotional tumult and the sisterhood that kept them going. These were richly complex women—successful in their careers but deeply frustrated with love and family. The book made McMillan a household name when it became one of the best-selling works of fiction in 1992. Critics railed against her — the same way they rail against Tyler Perry now — for not being imaginative or ambitious enough in her prose and exploring subject matter that focused too much on the intersection of class, gender, and Black heterosexual desire without interrogating the racism, sexism, or socioeconomic volatility that impacts the way Black folks live in America. But McMillan, like Perry, was connecting with an audience that rarely saw themselves imprinted in fiction or television or film. We all knew women like Savannah and Robin and Gloria and Bernadine — glamorous, vulnerable, impulsive, passionate, feisty, human. These were real women who could have easily been our sisters or our favorite aunties. I was seven or eight when I found my mother’s copy of Waiting to Exhale in her bedroom. I wouldn’t read it fully until I was a teenager, but I was captivated by the cover, the brown faceless silhouettes dressed in sharp, vibrant clothes. The cover looked like the contemporary Black art my mama and all her sisterfriends — my aunties — had in their apartments. I would lay in bed with her as she read, curled up in her warmth — lost in my own (age-appropriate) adventure.

Given its success, a film adaptation of Waiting to Exhale was inevitable. Forest Whitaker made his directorial debut with the film, and Angela Bassett, Lela Rochon, Loretta Devine, and Whitney were cast in the lead roles. At last Whitney had a nuanced role, one that required more of her than The Bodyguard and The Preacher’s Wife — films that were ostensibly built around the marvel of her singing voice. Savannah Jackson wasn’t a superstar pop diva being stalked or a neglected wife visited by a debonair angel. She was a weary woman who had reached great heights in her career but was deeply frustrated by her romantic prospects and her meddling mother. Savannah was a woman in search of peace of mind and a love that was meaningful. Like her sisterfriends, she was holding her breath for Mr. Right and tired of entertaining all the Mr. Wrongs who drifted into her life and made her shrink herself and put her needs second. Released around Christmas in 1995, Waiting to Exhale made history as the first film with all-Black female leads to open at number one at the box office. The popularity of the book and its blockbuster film adaptation were influential in normalizing middle-class Black women in the popular cultural consciousness. Studios were then eager to greenlight slickly produced soap operas exploring the Black middle class through ensemble family dramas and romantic comedies — far different from the hood films pouring out of Hollywood that coincided with the popularity of hip-hop and confronted the tumult of Black life in inner cities across the country. Whitney, like her onscreen character, was a woman in her early thirties. She had had a few years of marriage and motherhood under her belt, and twice as many as a superstar entertainer. She was worn out from the unkind press, the criticism of her personal life, of her music, and the nagging questions of authenticity.

Waiting to Exhale was pivotal in helping her change the narrative in a way she hadn’t been able to before. Whitney melted into the role of Savannah — a woman who had it all but somehow couldn’t snag a man who wasn’t a trifling dog. Whitney was sharp and funny in her performance, but more than that, she took the weariness her character lived in and merged it with her own pain. We didn’t know the depths of her personal sorrows yet. We suspected things were bad between her and Bobby. The tabloids churned out stories of Bobby’s infidelity and partying, and there was gossip that Whitney was a standoffish diva on set, chatter her co-stars attempted to silence. Years later, after she was long gone, we learned that Whitney actually overdosed on cocaine while shooting the film in Arizona. Whitney’s issues with drugs were still a secret from the general public, which again was only possible because we weren’t yet in a time when celebrity news was a twenty-four-hour machine. As far as we knew, Whitney was just a woman who appeared to be in a toxic marriage.

Excerpted from Didn’t We Almost Have It All: In Defense of Whitney Houston by Gerrick Kennedy published by Abrams Press ©2022.